Christian Church

Christian Church and church (Greek kyriakon (κυριακόν), "thing belonging to the Lord"; also ekklesia (ἐκκλησία) (Latinized as ecclesia, "assembly") are used to denote both a Christian association of people and a place of worship. In the phenomenological sense there are many such associations of people that call themselves Christian churches. In the New Testament the term ἐκκλησία (church or assembly) is used for local communities and in a universal sense to mean all believers.[1] Since heresy is seen as separating from the Church, the phrase "all believers" is ambiguous, and some churches, such as the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox churches, hold that that those who, though called Christians, are out of communion with them are not, in the full sense, part of the Church. Both consider their own Church as "the one true Church."

Contents |

Etymology

Mat16:18 "... and upon this rock I will build my church". This is the first reference of this term introduced by Christ in the context of a faith-based entity and the complex context into which it has evolved. The English language word "church" is from the Old English word cirice, derived from West Germanic *kirika, which in turn comes from the Greek κυριακή kuriakē, meaning "of the Lord" (possessive form of κύριος kurios "ruler, lord"). Kuriakē in the sense of "church" is most likely a shortening of κυριακὴ οἰκία kuriakē oikia ("house of the Lord") or ἐκκλησία κυριακή ekklēsia kuriakē ("congregation of the Lord").[2] Christian churches were sometimes called κυριακόν kuriakon (adjective meaning "of the Lord") in Greek starting in the 4th century, but ekklēsia and βασιλική basilikē were more common.[3]

The Greek word ekklēsia, literally "assembly, congregation, council", is the traditional term referring to the Christian Church. Most Romance and Celtic languages use derivations of this word, either inherited or borrowed from the Latin form ecclesia, which is used in English to denote either a particular local group, or the whole body of the faithful.

The word is one of many direct Greek-to-Germanic loans of Christian terminology, via the Goths. The Slavic terms for "church" (Old Church Slavonic црькꙑ [crĭky], Russian церковь [cerkov’]) are via the Old High German cognate chirihha.

History

The early Church originated in Roman Judea in the first century AD, founded on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth who is believed by Christians to be the Son of God and Christ the Messiah. It is usually thought of as beginning with Jesus' Apostles. According to scripture Jesus commanded them to spread his teachings to all the world.

Springing out of the first century Jewish faith, from Christianity's earliest days, Christians accepted non-Jews (Gentiles) without requiring them to fully adopt Jewish customs (such as circumcision).[Acts 10-15] [4] The parallels in the Jewish faith are the Proselytes, Godfearers, and Noahide Law, see also Biblical law in Christianity. Some think that conflict with Jewish religious authorities quickly led to the expulsion of the Christians from the synagogues in Jerusalem[5] (see also Council of Jamnia and List of events in early Christianity).

The Church gradually spread through the Roman Empire and outside it, gaining major establishments in cities such as Jerusalem, Antioch, and Edessa.[6][7][8] It also became a widely persecuted religion. It was condemned by the Jewish authorities as a heresy (see also Rejection of Jesus). The Roman authorities persecuted it because, like Judaism, its monotheistic teachings were fundamentally foreign to the polytheistic traditions of the ancient world and a challenge to the imperial cult.[9] Other teachings of Christianity, such as the call to chastity and the prohibition on homosexual practise, also made it unpopular. Despite this the Church grew rapidly until finally legalized and then promoted by Emperors Galerius and Constantine in the fourth century.

A major controversy as the Church was being formalized was the Arianism vs. Trinitarianism debate which occupied the Church during the fourth century.[10][11] On February 27, 380, the Roman Empire officially adopted the Trinitarian version of Christianity as its state religion. Prior to this date, Constantius II (337-361) and Valens (364-378) had personally favored Arian or Semi-Arian forms of Christianity, but Valens' successor Theodosius I supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed from the 1st Council of Nicea.

On this date, Theodosius I decreed that only the followers of Trinitarian Christianity were entitled to be referred to as Catholic Christians, while all others were to be considered to be practicers of heresy, which was to be considered illegal. In 385, this new legal authority of the Church resulted, in the first case of many to come, in the capital punishment of a heretic, namely Priscillian.[12][13] In the several centuries of state sponsored Christianity that followed, pagans and "heretical" Christians were routinely persecuted by the Empire and the many kingdoms and countries that later occupied the place of the Empire,[14] but some Germanic tribes remained Arian well into the Middle Ages[15] (see also Christendom).

The Church within the Roman Empire was organized under metropolitan sees, with five rising to particular prominence and forming the basis for the theory of the Pentarchy. Of these five, one was in the West (Rome) and the rest in the East (Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria).[16] Even after the split of the Roman Empire the Church remained a relatively united institution (apart from Oriental Orthodoxy and some other groups which separated from the rest of the Church earlier). The Church came to be a central and defining institution of the Empire, especially in the East or Byzantine Empire. In particular, Constantinople would come to be seen as the center of the Christian world, owing in great part to its economic and political power.[17][18]

Once the Western Empire fell to Germanic incursions in the 5th century, the (Roman) Church for centuries became the primary link to Roman civilization for Medieval Western Europe[19] and an important channel of influence in the West for the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, emperors. While, in the West, Christianity struggled as the so-called orthodox Church competed against the Arian Christian and pagan faiths of the Germanic rulers and spread outside what had been the Empire to Ireland and Scandinavia, in the East Christianity spread to the pagan Slavs, establishing the Church in what is now Russia, Central Europe and Eastern Europe.[20] The reign of Charlemagne in Western Europe is particularly noted for bringing the last major Western Arian tribes into communion with Rome, in part through conquest and forced conversion.

Starting in the 7th century the Islamic Caliphates rose and gradually began to conquer larger and larger areas of the Christian world.[20] Excepting North Africa and most of Spain, northern and western Europe escaped largely unscathed by Islamic expansion, in great part because richer Constantinople and its empire acted as a magnet for the onslaught.[21] The challenge presented by the Muslims would help to solidify the religious identity of eastern Christians even as it gradually weakened the Eastern Empire.[22] Even in the Muslim World, the Church survived (e.g., the modern Copts, Maronites, and others) albeit at times with great difficulty.[23][24]

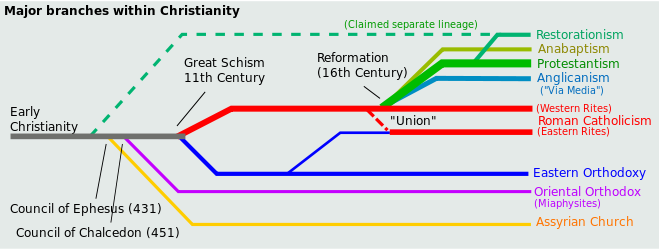

Although there had long been frictions between the Bishop of Rome (i.e., the Western Pope) and the eastern patriarchs within the Byzantine Empire, Rome's changing allegiance from Constantinople to the Frankish king Charlemagne set the Church on a course towards separation. The political and theological divisions would grow until Rome and the East excommunicated each other in the 11th century, ultimately leading to the division of the Church into the Western (Roman Catholic) and Eastern (Eastern Orthodox) Churches.[20]

As a result of the redevelopment of Western Europe, and the gradual fall of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Arabs and Turks (helped by warfare against Eastern Christians). The final Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD resulted in Eastern scholars fleeing the Moslem hordes bringing ancient manuscripts to the West, which was a factor in the beginning of the period of the Western Renaissance there. Rome came to be seen by the Western Church as Christianity's heartland.[25] Some Eastern churches even broke with Eastern Orthodoxy and entered into communion with Rome. The changes brought on by the Renaissance eventually led to the Protestant Reformation during which the Protestant Lutheran and the Reformed followers of Calvin, Hus, Zwingli, Melancthon, Knox, and others split from the Roman Catholic Church. At this time, a series of non-theological disputes also led to the English Reformation which led to the independence of the Anglican Communion. Then during the Age of Exploration and the Age of Imperialism, Western Europe spread the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant and Reformed Churches around the world, especially in the Americas.[26][27] These developments in turn have led to Christianity's being the largest religion in the world today.[28]

Related concepts

Orthodox Church and orthodox faith. These terms, with lower-case O, and thus distinguished from the term Orthodox Church, have been used to distinguish the true Church from heretical groups. The term became especially prominent in referring to the doctrine of the Nicene Creed and, in historical contexts, is often still used to distinguish this first "official" doctrine from others.[11]

Body of Christ (cf. 1Cor 12:27) and Bride of Christ (cf. Rev 21:9; Eph 5:22-33. These terms are used to refer to the total community of Christians seen as interdependent in a single entity headed by Jesus Christ.[29]

Visible and invisible Church. On this, see below.

Church Militant and Church Triummphant (Ecclesia Militans, Ecclesia Triumphans) These terms, taken together, are used to express the concept of a united Church that extends beyond the earthly realm into Heaven.[30] The term Church Militant comprises all living Christians while Church Triumphant comprises those in Heaven.

Church Suffering, or Church Expectant. A Roman Catholic concept encompassing those Christians in Purgatory, no longer part of the Church Militant and not yet part of the Church Triumphant.

Communion of Saints. This term expresses the idea of a union in faith and prayer that binds all Christians regardless of geographical distance or separation by death. In Roman Catholic theology it involves the Church Militant, the Church Triumphant, and also the Church Suffering.[31]

Orthodox tradition

The term orthodox is generally used to distinguish the faith or beliefs of the "true Church" from other doctrines which disagree, traditionally referred to as heresy.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy each claim to be the original Christian Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church bases its claim primarily on its assertion that it holds to traditions and beliefs of the original Christian Church. It also states that 4 out of the 5 sees of the Pentarchy (excluding Rome) are still a part of it.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches' claims are similar to those of the Eastern Orthodox Church, excluding the claim to 4 of the 5 sees of the Pentarchy.

The importance of identity of tradition and belief with the original Christian Church can be seen as originating with the biblical proscriptions against false prophets. "Orthodoxy" means both "true glory" and "correct teaching", and this theological term is explicitly used by Orthodox Christians as a shorthand way to refer to themselves as "the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic, Orthodox and Orthoprax, Church of Jesus Christ and His saints." In the same manner, the Roman Catholic Church describes itself as orthodox, meaning having possession of the whole faith. Other Christian denominations, who do not accept the claims of this Church to be the sole orthodox Church refer to her as the Eastern Orthodox Church.

This concept of "orthodoxy" began to take on particular significance during the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine I, the first to actively promote Christianity. Constantine convened the first Ecumenical Council, the Council of Nicea, which attempted to provide the first universal creed of the Christian faith.

The major issue of this and other councils during the fourth century was the christological debate between Arianism and Trinitarianism. Trinitarianism is the official doctrine of the Catholic Church and is strongly associated with the term "orthodoxy", although some modern non-trinitarian churches dispute this usage. Churches that subscribe to the Nicene Creed, the first official Trinitarian creed, are sometimes referred to as "orthodox"

Roman Catholic tradition

"The Holy Roman Catholic and Apostolic Church is the only flock of which Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is the only Shepherd." (Catholic Book of Prayers, Pg. 236, "One Flock, One Shepherd")[32]

The papal encyclical Mystici Corporis expresses the dogmatic ecclesiology of the Catholic Church thus: "if we would define and describe this true Church of Jesus Christ– which is the One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, Roman Church– we shall find no expression more noble, more sublime, or more divine, than the phrase which calls it ‘the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ." The Second Vatican Council's dogmatic constitution Lumen Gentium further declares that "the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic, ... constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him".[33][34] A 2007 declaration[35] of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith clarified that, in this passage, "'subsistence' means this perduring, historical continuity and the permanence of all the elements instituted by Christ in the Catholic Church, in which the Church of Christ is concretely found on this earth", and added:."It is possible, according to Catholic doctrine, to affirm correctly that the Church of Christ is present and operative in the churches and ecclesial Communities not yet fully in communion with the Catholic Church, on account of the elements of sanctification and truth that are present in them. Nevertheless, the word 'subsists' can only be attributed to the Catholic Church alone precisely because it refers to the mark of unity that we profess in the symbols of the faith (I believe... in the 'one' Church); and this 'one' Church subsists in the Catholic Church."

Protestant and Anglican traditions

Since the Protestant Reformation, most Protestant denominations interpret "catholic", especially in its creedal context, as referring to the concept of the eternal church of Christ and the Elect, referenced in the Bible in phrases such as "body of Christ"[1 Cor. 12:27] and "great cloud of witnesses".[Heb. 12:1] This Protestant interpretation of the words "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church" in the Nicene Creed identifies exclusively with the Church Triumphant—the church that exists "in heaven" or in eternity as opposed to the Church Militant—the communion of the faithful here on Earth. They view this understanding of "catholic"—written with a lower-case "c"—as necessarily distinct from any concrete expression in an institutional Church.

Anglicans generally understand their tradition as a branch of the historical Catholic Church and as a via media (middle way) between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Christianity on the one hand, and Protestantism on the other.

Apostolic succession

_-_The_Last_Supper_(1495-1498).jpg)

"Apostolic succession" is a doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Oriental Orthodox churches, the Anglican Communion and others. The doctrine asserts that the bishops of the "true Church" enjoy the favor or grace of God as a result of legitimate and unbroken sacramental succession from Jesus' apostles.[36] According to this doctrine, modern bishops, therefore, must be viewed as part of an unbroken line of leadership in succession from the original apostles: though they do not have the authority and powers granted uniquely to the apostles, they are the apostles' successors in governing the Church.[37]

Like the churches mentioned above, Protestants see the authority given to the apostles as unique, proper to apostles alone, but they conclude from this that any doctrine of a succession to the apostles by bishops is to be rejected. The Protestant view of ecclesiastical authority differs accordingly.[36]

Visible and the invisible church

Many Protestants believe that the Church, as described in the Bible, has a twofold character that can be described as the visible and invisible church.

In this view, the Church invisible consists of all those from every time and place who are vitally united to Christ through regeneration and salvation and who will be eternally united to Jesus Christ in eternal life. The universal, invisible church refers to the "invisible" body of the elect who are known only to God, and contrasts with the "visible church"—that is, the institutional body on earth which preaches the gospel and administers the sacraments. Every member of the invisible church is considered saved, while the visible church contains some individuals who are saved and others who are unsaved.[comp. Mt. 7:21-24] This concept has been attributed to St Augustine of Hippo as part of his refutation of the Donatist sect,[39] but others question whether Augustine really held to some form of an "invisible true Church" concept.[40]

The Church visible, in this same view, consists of all those who visibly join themselves to a profession of faith and gathering together to know and serve the Head of the Church, Jesus Christ. It exists globally in all who identify themselves as Christians and locally in particular places where believers gather for the worship of God. The visible church may also refer to an association of particular churches from multiple locations who unite themselves under a common charter and set of governmental principles. The church in the visible sense is often governed by office-bearers carrying titles such as minister, pastor, teacher, elder, and deacon.

For the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, making a real distinction between "the heavenly and invisible Church, alone true and absolute", and "the earthly Church (or rather 'the churches') imperfect and relative" is a "Nestorian ecclesiology"[41]

Roman Catholic theology reacted against the Protestant concept of a purely invisible Church by stressing the visible aspect of the Church founded by Christ; but in the twentieth century the Catholic Church has placed more stress on the interior life of the Church as a supernatural organism. In an encyclical it identified the Church with the Mystical Body of Christ.[42][43] This encyclical rejected two extreme views of the Church:[44]

- A rationalistic or purely sociological understanding of the Church, according to which she is merely a human organization with structures and activities, is mistaken. The visible Church and its structures do exist but the Church is more, as she is guided by the Holy Spirit:

Although the juridical principles, on which the Church rests and is established, derive from the divine constitution given to it by Christ and contribute to the attaining of its supernatural end, nevertheless that which lifts the Society of Christians far above the whole natural order is the Spirit of our Redeemer who penetrates and fills every part of the Church.[45]

- An exclusively mystical understanding of the Church is mistaken as well, because a mystical "Christ in us" union would deify its members and mean that the acts of Christians are simultaneously the acts of Christ. The theological concept una mystica persona (one mystical person) refers not to an individual relation but to the unity of Christ with the Church and the unity of its members with him in her.[46]

Church government

Major forms of church government include hierarchical (Anglican, Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholic), presbyterian (rule by elders), and independent (Baptist, charismatic, other forms of in dependency). Before the Protestant Reformation clergy were universally understood to gain their authority through apostolic succession.

Metaphors

Christian scriptures use a wide range of metaphors to describe the Church. These include:

- Family of God the Father[Eph. 3:14-15] [2 Cor. 6:18]

- Brothers and sisters with each other in God's family[Matt. 12:49-50]

- Bride of Christ[Eph. 5:31-32]

- Branches on a vine[Jn. 15:5]

- Olive tree[Rom. 11:17-24]

- Field of crops[1 Cor. 3:6-9]

- Building[1 Cor. 3:9]

- Harvest[Matt. 13:1-30] [John 4:35]

- New temple and new priesthood with a new cornerstone[1 Pet. 2:4-8]

- God's house[Heb. 3:3-6]

- Pillar and foundation the truth[1 Tim. 3:15]

- Body of Christ[1 Cor. 12:12-27]

- Temple of the Holy Spirit[2 Cor. 6:16]

Divisions and controversies

Today there is a wide diversity of Christian groups, with a variety of different doctrines and traditions. These controversies between the various branches of Christianity naturally include significant differences in their respective ecclesiologies.

One universal church

The phrase One, holy, catholic and apostolic Church' appears in the Nicene Creed (μίαν, ἁγίαν, καθολικὴν καὶ ἀποστολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν) and, in part, in the Apostles' Creed ("the holy catholic church", sanctam Ecclesiam catholicam, which in Greek would be: ἁγίαν καθολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν).[47][48] The phrase is intended to set forth the four marks, or identifying signs, of the Christian Church—unity, holiness, universality, and apostolicity—and is based on the premise that all true Christians form a single united group founded by the apostles.[49]

The word "catholic" is derived from the Greek adjective καθολικός pronounced katholikos, which means "general" or "universal".[50] Applied to the Church, it implies a calling to spread the faith throughout the whole world and to all ages. It is also thought of as implying that the Church is endowed with all the means of salvation for its members. In this sense the Church is taken by Christian theology to refer to the single, universal community of faithful. Baptism and communion signifies membership of the Church. Excommunication is not expulsion from the Church, and is a remedial denial of the sacraments to a baptized Christian that does not invalidate their baptism.

Saint Ignatius of Antioch, the earliest known writer to use the phrase "the catholic church", excluded from the Church heterodox groups whose teaching and practice conflicted with those of the bishops of the Church, and considered that they were not really Christians. In keeping with this idea, many churches and communions consider that those whom they judge to be in a state of heresy or schism from their church or communion are not part of the catholic Church. This is the view of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

The Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church each regard themselves as the one true and unique church of Christ, and claim to be not just a Christian Church but the original Church founded by Christ, preserving unbroken the original teaching and sacraments. The Roman Catholic Church teaches that "the one Church of Christ, as a society constituted and organized in the world, subsists in the Catholic Church, governed by the Successor of Peter and the bishops in communion with him. Only through this Church can one obtain the fullness of the means of salvation since the Lord has entrusted all the blessings of the New Covenant to the apostolic college alone whose head is Peter."[52] Similarly, the Eastern Orthodox Church believes it is "the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, founded by Jesus Christ and His apostles. It is organically and historically the same Church that came fully into being at Pentecost."[53] They see the members of other churches as linked in only an imperfect way with the one true Church, recognising Protestants not as churches but as ecclesial or specific faith believing communities.[54]

Many other Christian groups take the view that all denominations are part of a symbolic and global Christian church which is a body bound by a common faith if not a common administration or tradition. Like the Roman Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church and some others have always referred to themselves as the Catholic church.[55] Oriental Orthodoxy shares this view, seeing the Churches of the Oriental Orthodox communion as constituting the one true Church. In the West the term Catholic has come to be most commonly associated with the Roman Catholic Church because of its size and influence in the West (although in formal contexts most other churches still reject this naming).

Denominations

These Churches believe that the term one in the Nicene Creed describes and prescribes a visible institutional unity, not only geographically throughout the world, but also historically throughout history. They see unity as one of the four marks that the Creed attributes to the genuine Church, and the essence of a mark is that it be visible. A Church whose identity and belief varied from country to country and from age to age would not be "one" in their estimation.

In the New Testament, the word "Church" or "assembly"—(translations for ekklesia)—normally refers to believers on earth, and they conclude that the Creed's description "one" must be applicable to the Church on earth and must not be reserved for some eschatological reality. The only exception to the normal New Testament use of the word "ἐκκλησία" is the mention of the "ἐκκλησία of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven."[Heb. 12:23] Even there the Christians to whom the letter is addressed are associated with that heavenly Church ("you have come to….") In line with this passage, the ancient Churches mentioned see the saints too—that is, the holy dead—as part of the one Church and not as ex-members, so that Christians both in the present life and the afterlife form a single Church.

Many Baptist and Congregationalist theologians accept the local sense as the only valid application of the term church. They strongly reject the notion of a universal (catholic) church. These denominations argue that all uses of the Greek word ekklesia in the New Testament are speaking of either a particular local group or of the notion of "church" in the abstract, and never of a single, worldwide church.[56][57]

Many Anglicans, Lutherans, Old Catholics, and Independent Catholics view unity as a mark of catholicity, but see the institutional unity of the Catholic Church as manifested in the shared Apostolic Succession of their episcopacies, rather than a shared episcopal hierarchy or rites.

Reformed Christians hold that every person justified by faith in the Gospel committed to the Apostles is a member of "One, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church". From this perspective, the real unity and holiness of the whole church established through the Apostles is yet to be revealed; and meanwhile, the extent and peace of the church on earth is imperfectly realized in a visible way.

Other debates

Other debates include the following:

- Churchianity is a pejorative term used to describe practices of Christianity that are viewed as placing a larger emphasis on the habits of church life or the institutional traditions the Christian Church (Ecclesia) than on the teachings of Jesus. It can also be used to describe churches where the central focus has moved from Christ to the church. Hence the replacement of Christ with church in the word churchianity. The opposing position taken by the Orthodox Churches, the Anglican Communion and the Roman Catholic Church is that the Church is very much essential (Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus), based on the close union between Christ and the Church as described in Biblical passages such as Epistle to the Ephesians (see Bride of Christ). Orthodox theology, on the other hand, sees Protestant worship and piety as being too man centered, especially when centered on a celebrity pastor and on factions rather than on Christ, which they claim becomes the center in traditional piety.

- There are many opinions as to the ultimate fate of the souls of individuals who are not part of a particular institutional church, i.e., members of a particular church may or may not believe that the souls of those outside their church organization can or will be saved.

- There have always been differing opinions as to the divinity of God, the Son and or his unity with God, the Father. Although historically the most significant debate in this arena was the Arianism and trinitarianism debate in the Roman Empire, debates in this realm have occurred throughout Christian history.

- It has been debated whether or not the Christian Church is in fact a unified heavenly institution with the earthly institutions relegated to secondary status.

See also

- Body of Christ

- Bride of Christ

- Catholic Church

- List of popes

- Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral

- Christendom

- Christian ecumenism

- Christianity

- Church architecture

- Church militant and church triumphant

- Churching of women

- Evangelical Catholic

- Germanic Christianity

- High Church, such as Anglicanism

- History of Christianity

- Jesus Christ

- Kingdom of God

- List of Christian denominations

- List of Christian denominations by number of members

- Low Church, such as Evangelicalism

- Orthodox Church

- Priesthood of all believers

- Stone-Campbell Movement

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) (Instrumental)

- Churches of Christ, (A Cappella)

- Christian Churches and Churches of Christ (Independent)

- Evangelical Christian Church in Canada (Christian Disciples)

- World Churchs Of Christ

- Unam Sanctam

- Indian National Christian Congress

Notes

- ↑ McKim, Donald K. Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms. Westminster John Knox Press, 1996

- ↑ Harper, Douglas (2001). "church". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=church. Retrieved 2008-01-18. "O.E. cirice "church," from W.Gmc. *kirika, from Gk. kyriake (oikia) "Lord's (house)," from kyrios "ruler, lord."".

- ↑ Harper, Douglas (2001). "church". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=church. Retrieved 2008-01-18. "Gk. kyriakon (adj.) "of the Lord" was used of houses of Christian worship since c.300, especially in the East, though it was less common in this sense than ekklesia or basilike.".

- ↑ Church as an Institution, Dictionary of the History of Ideas, University of Virginia Library [1]

- ↑ An Overview of Christian History, Catholic Resources for Bible, Liturgy, and More [2]

- ↑ Acts of the Apostles, New Advent

- ↑ Donald H. Frew, Harran: Last Refuge of Classical Paganism Colorado State University Pueblo [3]

- ↑ From Jesus to Christ: Maps, Archaeology, and Sources: Chronology, PBS, retrieved May 19, 2007 [4]

- ↑ Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, Christianity and the Roman Empire: Reasons for persecution, Ancient History: Romans, BBC Home, retrieved May 10, 2007 [5]

- ↑ Michael DiMaio, Jr., Robert Frakes, Constantius II (337-361 A.D.), De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families [6]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Michael Hines, Constantine and the Christian State, Church History for the Masses [7]

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/theodcodeXVI.html. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ↑ "Lecture 27: Heretics, Heresies and the Church". 2009. http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture27b.html. Retrieved 2010-04-24. Review of Church policies towards heresy, including capital punishment (see Synod at Saragossa).

- ↑ Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale University Press, September 23, 1997

- ↑ Christianity Missions and monasticism, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online [8]

- ↑ Deno Geanakoplos, A short history of the ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople, Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarch, retrieved May 20, 2007 [9]

- ↑ "MSN Encarta: Orthodox Church, retrieved May 12, 2007". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwQxJnKj.

- ↑ Arias of Study: Western Art, Department of Art History, University of Wisconsin, retrieved May 17, 2007 [10]

- ↑ What were the Dark Ages?, GotQuestions.org, retrieved May 20, 2007

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 CHRISTIANITY IN HISTORY, Dictionary of the History of Ideas, University of Virginia Library [11]

- ↑ The Byzantine Empire, byzantinos.com

- ↑ BYZANTINE ICONOCLASM AND POLITICAL EARTHQUAKE OF ARAB CONQUESTS – AN EMOTIONAL ‘GUST’, This Century's Review, retrieved May 24, 2007 [12]

- ↑ The History of the Copts, California Academy of Sciences [13], retrieved May 24, 2007

- ↑ History of the Maronite Patriarchate, Opus Libani, retrieved May 24, 2007 [14]

- ↑ Aristeides Papadakis, John Meyendorff , The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy: The Church 1071-1453 A.D., St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, August 1994, ISBN 0-88141-057-8, ISBN 978-0-88141-057-0

- ↑ Christianity and world religions, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ South America:Religion, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents, Adherents.com [15]

- ↑ Saint Paul, the Apostle: The body of Christ, Encyclopedia Britannica [16]

- ↑ Karl Adam, The Spirit of Catholicism, Eternal Word Television Network, retrieved May 24, 2007 [17]

- ↑ "communion of saints", Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Catholic Book of Prayers, Pg. 236, Large-Print Edition; Nihil Obstat and Impramatur. 2005 copyright. Catholic Book Publishing Corp., New Jersey.

- ↑ Lumen gentium, 8

- ↑ In The Catholicity of the Church, p. 132, Avery Dulles noted that this document avoided explicitly calling the Church the "Roman" Catholic Church, replacing this term with the equivalent "which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him" and giving in a footnote a reference to two earlier documents in which the word "Roman" is used explicitly.

- ↑ Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Apostolic Succession, The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07.[18]

- ↑ Successors of the Apostles

- ↑ See Augsburg Confession, Article 7, Of the Church

- ↑ Justo L. Gonzalez (1970-1975). A History of Christian Thought: Volume 2 (From Augustine to the eve of the Reformation). Abingdon Press.

- ↑ Patrick Barnes, The Non-Orthodox: The Orthodox Teaching on Christians Outside of the Church

- ↑ Vladimir Lossky, The mystical theology of the Eastern Church (St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1976 ISBN 0-913836-31-1) p. 186

- ↑ Mystici Corporis Christi

- ↑ John Hardon, Definition of the Catholic Church

- ↑ Heribert Mühlen, Una Mystica Persona, München, 1967, p. 51

- ↑ Pius XII, Mystici Corporis Christi, 63

- ↑ S Tromp, Caput influit sensum et motum, Gregorianum, 1958, pp. 353-366

- ↑ Nicene Creed, The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Christian Classics Ethereal Library [19]

- ↑ Apostle's Creed, Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ↑ Kenneth D. Whitehead, Four Marks of the Church, EWTN Global Catholic Network [20]

- ↑ Tufts University: Perseus Digital Library: A Greek-English Lexicon

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage: Vatican City

- ↑ Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 162

- ↑ What is the Orthodox Church?

- ↑ "The expression sister Churches in the proper sense, as attested by the common Tradition of East and West, may only be used for those ecclesial communities that have preserved a valid Episcopate and Eucharist" (Note on the expression "sister Churches").

- ↑ Robert G. Stephanopoulos. "The Greek (Eastern) Orthodox Church in America". www.goarch.org. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. http://www.goarch.org/en/archdiocese/. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ 1689 London Baptist Confession

- ↑ Savoy Declaration

References

- University of Virginia: Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Christianity in History, retrieved May 10, 2007 [21]

- University of Virginia: Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Church as an Institution, retrieved May 10, 2007 [22]

- Christianity and the Roman Empire, Ancient History Romans, BBC Home, retrieved May 10, 2007 [23]

- Orthodox Church, MSN Encarta, retrieved May 10, 2007"Orthodox Church - MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwQxJnKj.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church [24]

- Mark Gstohl, Theological Perspectives of the Reformation, The Magisterial Reformation, retrieved May 10, 2007 [25]

- J. Faber, The Catholicity of the Belgic Confession, Spindle Works, The Canadian Reformed Magazine 18 (Sept. 20-27, Oct. 4-11, 18, Nov. 1, 8, 1969)-[26]

- Boise State University: History of the Crusades: The Fourth Crusade[27]

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: ARTICLE 9 "I BELIEVE IN THE HOLY CATHOLIC CHURCH": 830-831 [28]: Provides Roman Catholic interpretations of the term catholic

- Kenneth D. Whitehead, Four Marks of the Church, EWTN Global Catholic Network [29]

- Unity (as a Mark of the Church), New Advent [30]

- Apostolic Succession, The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05.[31]

- Gerd Ludemann, Heretics: The Other Side of Early Christianity, Westminster John Knox Press, 1st American ed edition (August 1996), ISBN 0-664-22085-1, ISBN 978-0-664-22085-3

- From Jesus to Christ: Maps, Archaeology, and Sources: Chronology, PBS, retrieved May 19, 2007 [32]

- Bannerman, James, The Church of Christ: A treatise on the nature, powers, ordinances, discipline and government of the Christian Church', Still Waters Revival Books, Edmonton, Reprint Edition May 1991, First Edition 1869.

- Grudem, Wayne, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester, England, 1994.

- Kuiper, R.B., The Glorious Body of Christ, The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh, 1967

- Mannion, Gerard and Mudge, Lewis (eds.), The Routledge Companion to the Christian Church, 2007

External links

- Vatican II, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium

- Reflections on the Church by Reid Monaghan

- Church Links

- Christianity vs. Churchianity

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||